Handicraft aspects

“Die Fäden (der Byssus) sind frisch schmuzig weiß, werden mit den Hauptmuskel abgeschnitten, kardätscht, gesponnen (zu drei Fäden gezwirnt), und vornämlich zu Strümpfen und Handschuhen (oft auch mit etwas Seide) verarbeitet, dann gewaschen, mit Citronensaft bestrichen und zwischen Papier heiß geplättet. Die Gewebe sind fein, gelbbraun, sehr glänzend und werden daher den seidenen vorgezogen.” (Leuchs 1835)

“The Pinna is torn off the rocks with hooks, and broken for the sake of its bunch of silk called Lanapenna, which is fold, in its rude state, for about fifteen carlini a pound, to women that wash it well with soap and fresh water. When it is perfectly cleansed of all its impurities, they dry it in the shade, straiten it with a large comb, cut off the useless root, and card the remainder; by which means they reduce a pound of coarse filaments to about three ounces of fine thread. This they knit into stockings, gloves, caps, and waistcoats; but they commonly mix a little silk as a strengthener. This web is of a beautiful yellow-brown, resembling the burnished gold on the back of some flies and beetles. I was told that the Lanapenna receives its gloss from being steeped in lemon juice, and being afterwards pressed down with a taylor’s goose.” (Swinburne 1783)

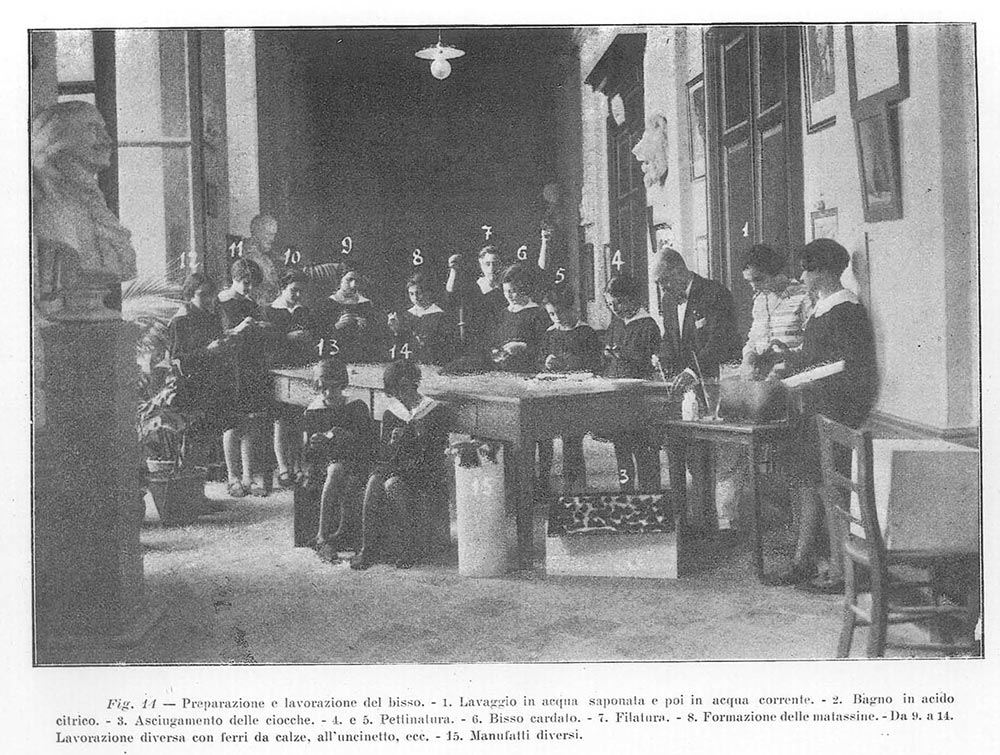

Almost everything we know today about the harvesting of the fan shell, the extraction of the fibre beard as well as the production and processing of sea silk, originates in reports from the 18th, 19th and the first half of the 20th century respectively. The procedures and the instruments used are essentially similar but display different local variations. In 1916, Basso-Arnoux describes this in particular detail for Sardinia and in 1928, Mastrocinque does so for Taranto. As an increasing number of Sardinian sea silk weavers are becoming known to the public within the project, the current state of the handicraft can also be described. Arianna Pintus shows it in a short video

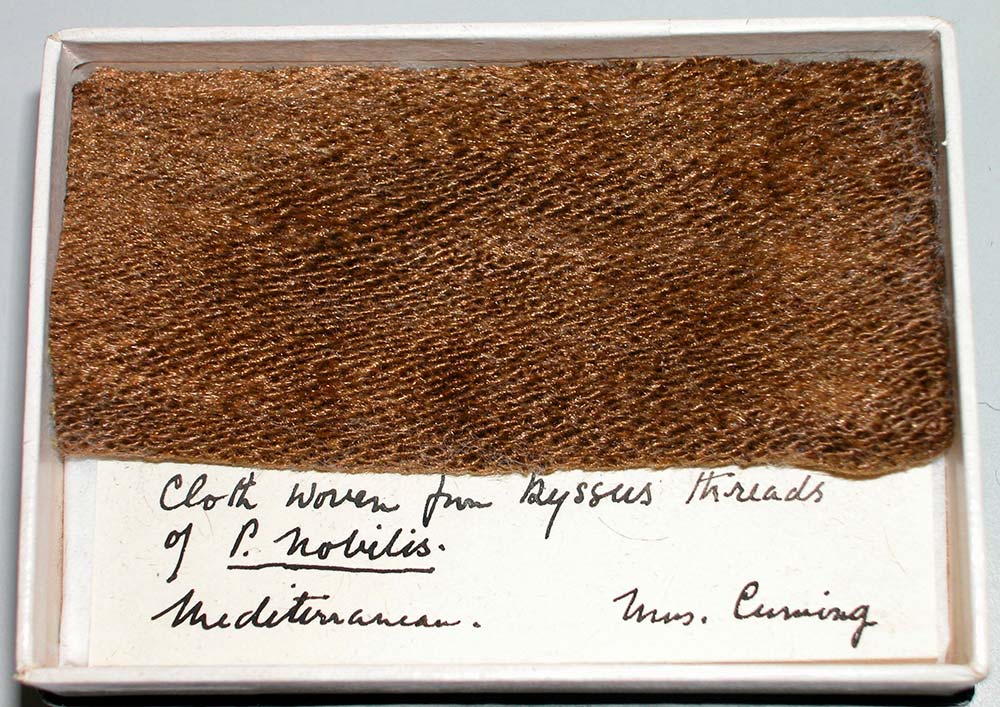

Since no antique textiles made of sea silk have been preserved, we do not know how they were processed. Almost half of all inventoried objects are simply plainly knitted, some have knitted patterns, or are crocheted. At the end of the 18th century, fabrics with woven or embroidered decorations made of sea silk are recorded – as they are still produced in Sardinia for illustrative purposes. In the first half of the 19th century, the processing of cleaned fibre beards into fur-like textile objects emerged, first in Taranto and, later, in Sardinia. Solid, woven fragments, in which sea silk merely forms the surface, pose particular questions.

When recording the tradition of the sea silk processing craft, one has to consider that this is not static. The individual steps and their meanings have probably changed over the centuries, depending on the economic, social and cultural environment, and have been adapted to the needs and expectations of each individual.

Extraction and cleaning of the raw material

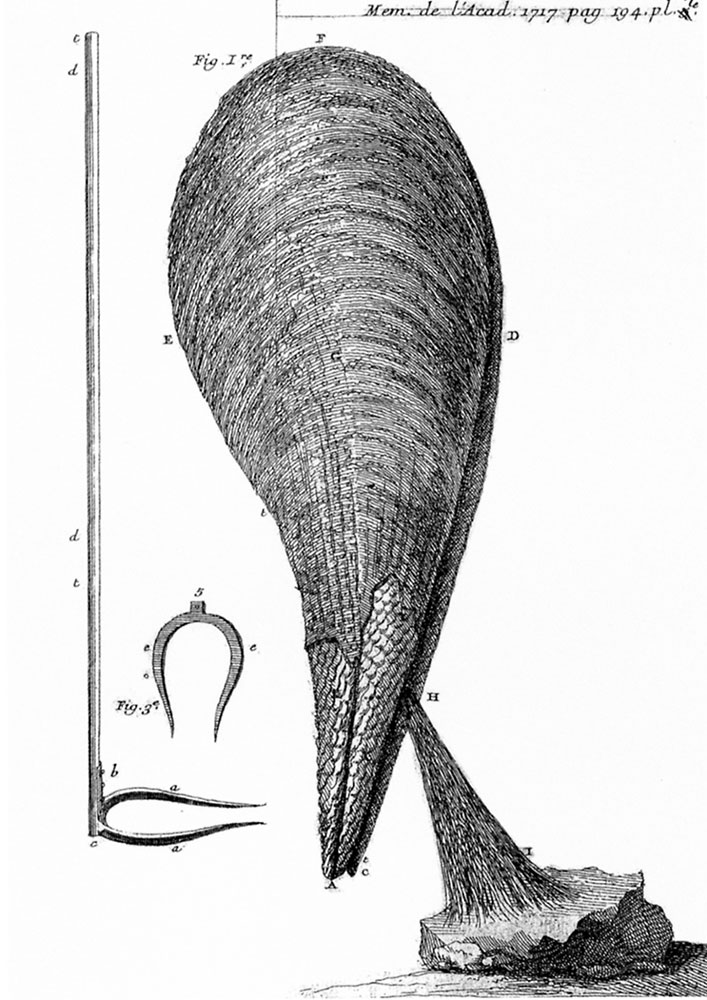

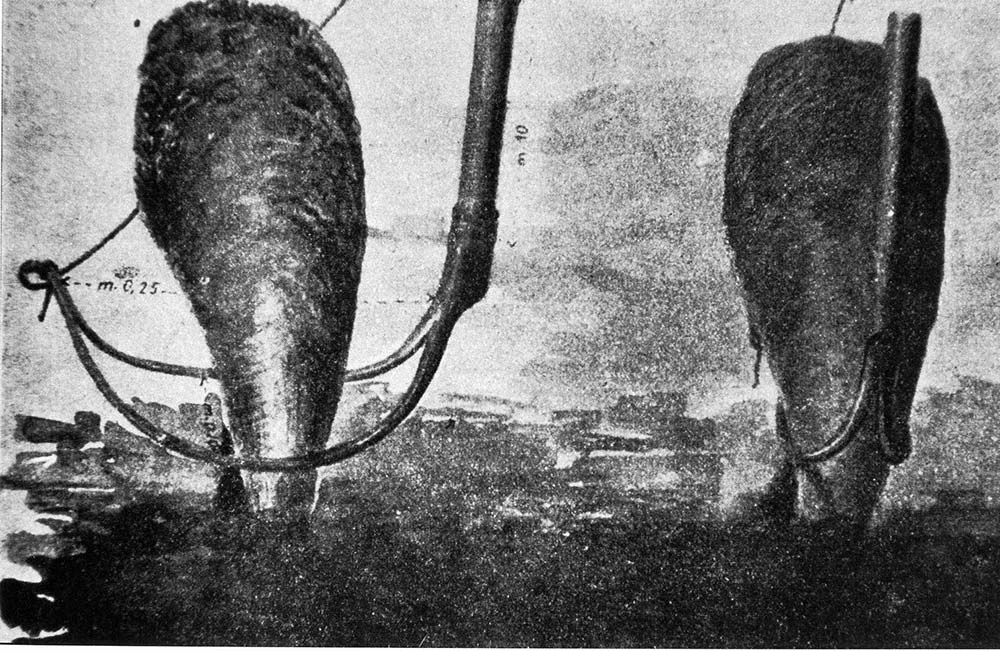

Where the fan shell was found in large populations, it was primarily a foodstuff. The meat of an adult shell can weigh up to one kilo. Opinions on the quality of the meat – from tough to fine – differ widely. Only the white, round adductor muscle is said to be a delicacy, similar to a great scallop. The fibre beard (byssus) was a by-product, like the shells, which were used for various purposes. The red mother-of-pearl was used to make buttons and mosaics – in Alghero, a whole bar counter is made of such mosaic stones. In antiquity, in the 3rd century BC, another use of the whole shell becomes evident: lead ingots are made by pouring the molten lead directly into half of an empty shell (Gosner 2021).

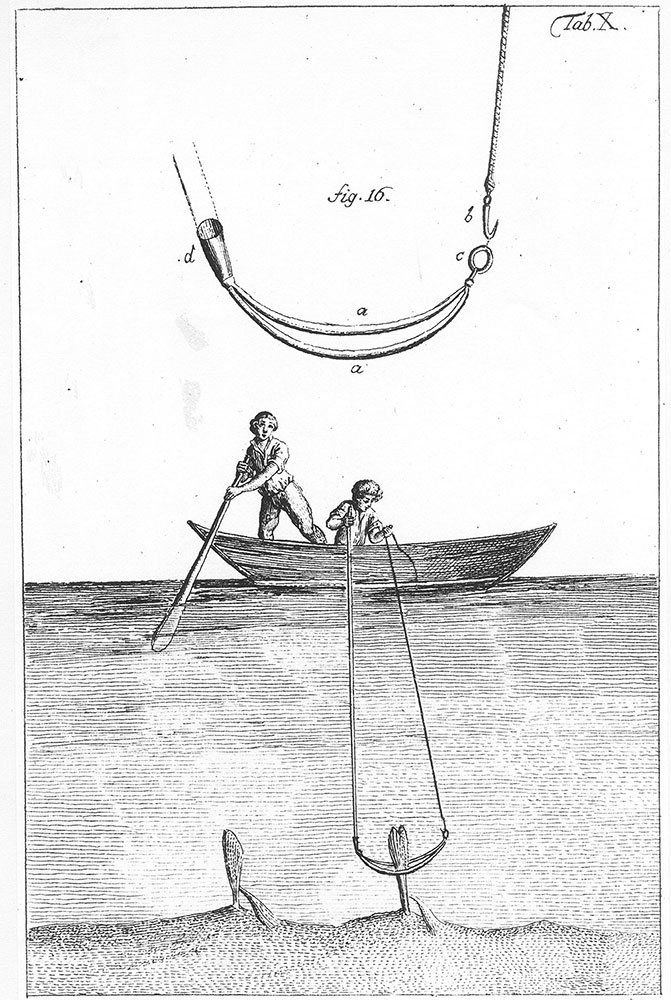

“This muscle is fished up with an iron, called pernonico, and the operation is thus performed. The instrument consists of two semicircular bars of iron … fastened together at each end, but three inches distant from each other in the centre. From one end to the other, the diameter is nine inches, and the cavity, or half diameter, is from four to five inches. At one end is a hollow handle … in which a pole, of the length required, may be fastened at pleasure; but at the other end is a ring … to which a cord … is made fast. As soon as a pinna is discovered, the iron is slowly let down to the ground over the shell, which is then twisted round, and drawn out.” (von Salis Marschlins 1795)

In the heyday of sea silk production, in the 18th and early 19th centuries, fan shells were ‘fished’ from the boat with various catching irons, tongs and forks, as the engraving from the 1793 book by the Swiss naturalist Carl Ulysses von Salis Marschlins illustrates. At the end of the 18th century, he travelled all over southern Italy, wrote several extensive reports about it and described the extraction and processing of the fibre beard in detail. At the beginning of the 20th century, a new fishing gear, which connects pincers with a shovel, was created in Taranto.

“When the fishermen have got a sufficient number of them, the shell is opened, and the silk, called at Taranto lana penna, is cut off the animal, and after being twice washed in tepid water, once in soap and water, and twice again in tepid water, is spread upon a table, and suffered to half dry in some cool and shady place. Whilst it is yet moist, it is softly rubbed and separated with the hand, and again spread upon the table to dry; and when thoroughly dry, it is drawn through a wide comb, and afterwards through a narrow one. Both these combs are of bone, and, except in size, are like hair combs. The silk thus combed belongs to the common sort, and is called extra dente; but that which is destined for finer works is again drawn through iron combs, or cards, there called scarde.” (von Salis Marschlins 1795) He continues: “It is then spun with a distaff and spindle, two or three threads of it being mixed with one of real silk; after which they knit not only gloves, stockings, and waistcoats, but even whole garments of it. When the piece is finished, it is washed in clean water, mixed with lemon juice; after which it is gently beaten between the hands, and finally smoothed with a warm iron. The most beautiful are of a brown cinnamon and glossy gold colour, producing a very rich and pleasing effect.”

The sisters Assuntina and Giuseppina Pes from Sant’Antioco in Sardinia were invited to the first congress dedicated to the theme of sea silk (and purple). It took place in 2013 in Lecce and was organised by the Università del Salento in collaboration with the University of Copenhagen. There, they demonstrated the whole production process to the fascinated audience, from cleaning the fibre beards to carding, spinning and weaving. Below are their own words (translated freely by the author):

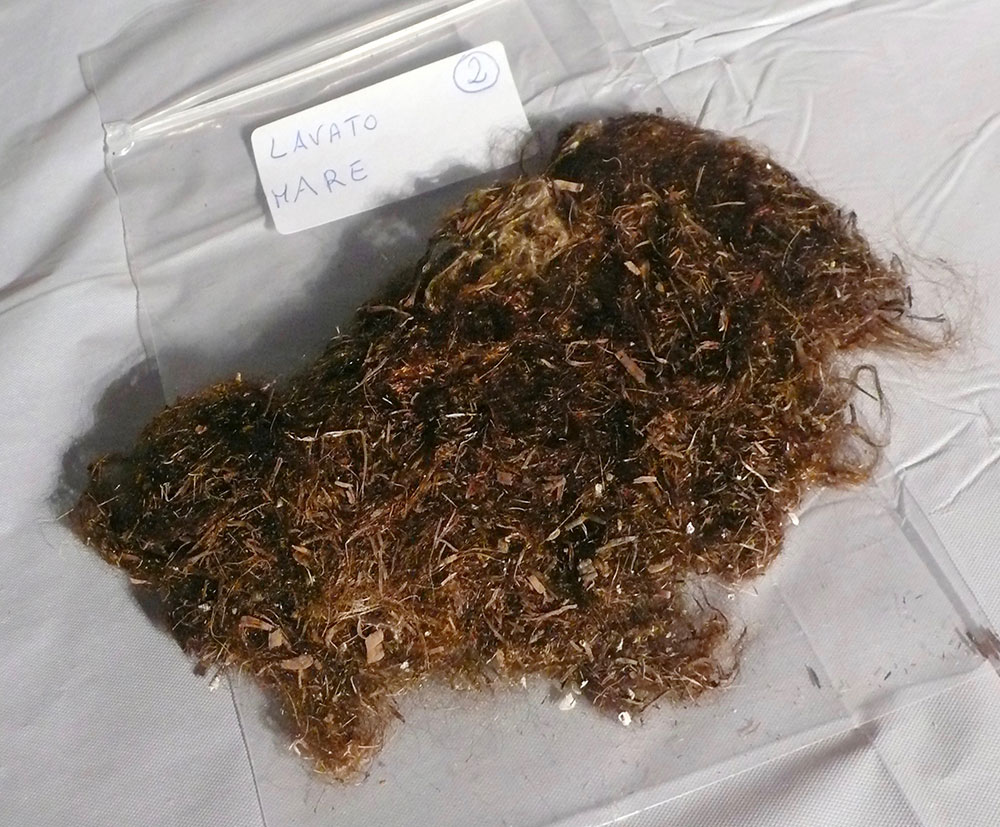

“The raw fibre beard (Byssus) is polluted with algae, small shells, stones and sand. Especially the fibre beards found on the beach look like mud balls and are hardly visible. The first cleaning is carried out in seawater, as the movement of the waves helps to free the fibres from the impurities more easily. The second washing process in fresh water takes a lot of time and patience until the salt in the sea water has dissolved. The remaining impurities are then removed manually. This is followed by a third bath in fresh water. Now the fibre beards are dried in the shade between two cloths. Then the dry fibre beard is lightly rubbed between the hands to separate the fibres and is checked for the last impurities. With a comb, the fibres are aligned for the first time.

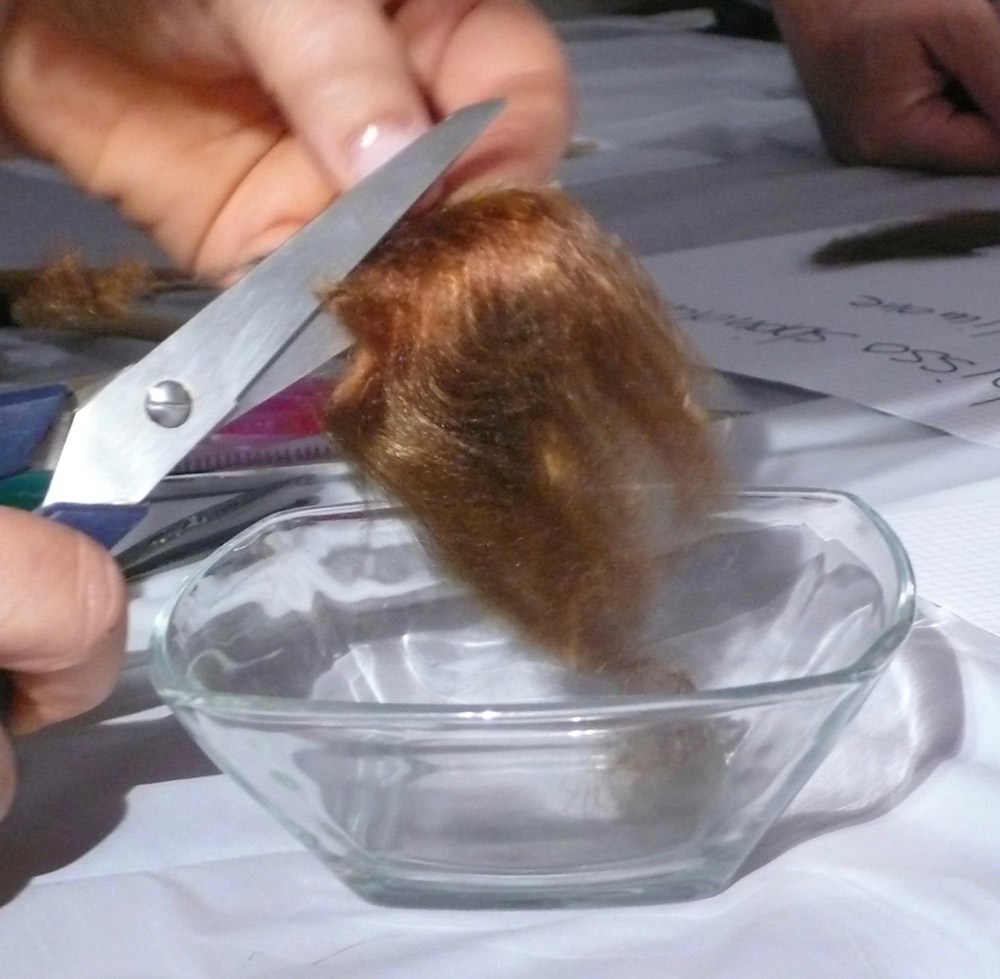

The next step is carding, a delicate process as the fibres are very fine and sensitive. The fibre beard is combed with a comb with fine steel pins – the individual fibres should remain attached to the remaining flesh of the mussel’s foot. This is followed by the last step: repeated carding with a very fine comb. The spinning is done with a short hardwood spindle. The whole process requires 2-3 days of work, depending on the size of the fibre beard and – above all – the length of the fibres”.

The natural colour of the cleaned and combed fibre beard of the Pinna nobilis varies, probably depending on the location. Possibly, it also depends on the age of the shell, and colours can range from bronze or copper, golden yellow, brown, olive green to black. In 1785, Swinburne called it “a beautiful yellow-brown, resembling the burnished gold on the back of some flies and beetles. I was told that the Lanapenna receives its gloss from being steeped in lemon juice, and being afterwards pressed down with a taylor’s goose.”

Two controversial and widely discussed questions in literature are whether sea silk can and has ever been dyed. To date, no dyed objects have been found. The predominant opinion is, however, that sea silk was sought due to its natural colour, which allows for concluding that no dyeing experiments were usually carried out. The photograph taken in the studio of the Sardinian weaver Arianna Pintus in Tratalias demonstrates how different the natural colour shades can be. The fact that a fibre beard has different shades in itself is shown beautifully by a partially cut byssus.

The 1805 encyclopedia of Krünitz confirms this in an article on the processing of sea silk: In contrast to other silk manufacturing processes, sea silk does not need any dyeing due to its natural inimitable brown, olive-green, shiny, golden yellow colour. This is apparently still true later, as Heinzelmann testified for Sardinia in 1852: “Der Vortheil bei diesem Zeug, Guacara genannt, ist, dass man nicht erst, wie bei der Seide, kostbare Färbereien bedarf.” (in English: The advantage of this stuff, called guacara, is that you do not need precious dyeing factories, as you do with mulberry silk).

It is important to differentiate between lightening the fibre and dyeing with dyes or pigments. It is undisputed that a soak in lemon juice or citric acid and the application of lemon juice to the fibres, the yarn or the finished object effectively lightens the fibres or the yarn or fabric. Others are convinced that sea silk can be dyed. “Ai fiocchi ed alle Stoffe puo essere dato pure il colore porpora, e qualsiasi altra tinta, essi conservano sempre la lucentezza serica.” (del Bene 1936), (in English: Flakes and fabrics can also be given the colour purple and any other colour, they always retain their silky sheen.) In 1936, Del Bene wrote a report, entitled Procedimento per le fabbricazzione di tessuti mediante la utillizzazione dei filamenti fibrosi della Pinna nobilis.

The results are shown in her later report from 1939, where various discolored and dyed patterns of sea silk are shown (Strippoli 2005); but it does not indicate which dyes were used. However, they are astonishingly similar to the dyeing tests carried out in 2010 by the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Testing and Research (EMPA) in St. Gallen, which used modern chemical dyes.

At the 2013 congress about sea silk and purple in Lecce, the artist Inge Boesken Kanold, who has been experimenting with real purple for decades, attempted dyeing with purple as well as applying purple pigments. The results are not convincing: the dyed sea silk fibres become only slightly darker, while the application of pigments shows an extremely unsatisfactory result. This is not surprising, since earlier attempts in Sant’Antioco had also failed. Italo Diana tried to dye sea silk with purple (from snails of the genus Muricidae) or with vegetable materials. Both failed: “Italo Diana tentò anche la tintura del bisso con la porpora ricavata dal murice ma non riuscì nell’intento; fallirono pure gli esperimenti di tintura mediante essenze vegetali.” (Carta-Mantiglia 2004)

In his Tesi di laurea of 1967/68: Aspetti e problemi dello sviluppo economico di Brindisi dal 1861 al 1881, De Castro reveals a new aspect, namely that in the past – the exact period he is referring to is unclear – the term industria del ‘bisso’ was erroneously used to refer to the purple industry: “In passato l’industria del ‘bisso’ o ‘porpora’, come erroneamente si chiamava da altri, era una delle principali della Provincia.” Could this be a reason for the thesis that sea silk was dyed with purple, as Luciana Basciu argues in her 1997 article Porpora e Bisso nell’antichità? “Tornando alla porpora si può ragionevolmente ipotizzare che il termine ‚porpora di Tiro‘ si riferisse unicamente al bisso tinto con il gasteropode Thais (sin. Purpura) haemastoma, e quindi di costo giustamente folle. Il bisso, che esiste ancora, non è un ‚lino sottile‘, come riportato in tutti i testi, ma una specie di seta ottenuta trattando i filamenti con cui i molluschi lamellibranchi delle specie Pinna nobilis e pinna regalis si ancorano al fondo.” (in English: Returning to purple, one can reasonably assume that the term ‘Tyrian purple’ referred only to byssus dyed with the gastropod Thais (syn. Purpura) haemastoma, and, therefore, at a justifiably insane cost. The byssus, which still exists, is not a ‘fine linen’, as reported in all texts, but a kind of silk obtained by treating the filaments with which the lamellibranch molluscs of the species Pinna nobilis and pinna regalis anchor themselves to the bottom.) As explained in the chapter on linguistic aspects → Byssus and byssus, in the Bible, the term bisso/Byssus does not stand for sea silk but for the finest linen. Therefore, Biblical pair of terms ‘byssus and purple’ refers to linen dyed with purple. In any case, the question arises as to why the golden sea silk should have been dyed with precious purple if the result was merely a slightly darker tone (Carta-Mantiglia 2004).

Further processing of the sea silk

The oldest fragment identified as sea silk dates from the 4th century AD. It was probably woven. Unfortunately, it was lost in the turmoil of World War II. It is not known whether whole dresses were ever woven from sea silk, as is often mentioned in literature. It is more likely that, again, the ancient term byssus was confused with sea silk. The oldest surviving object dates from the 14th century: a very simple cap knitted in stocking stitch.

Most of the preserved objects, a large part of which are gloves, are knitted. They were ideal gifts among the ecclesiastical and secular nobility, exclusive and shiny, small and easy to transport. At the beginning of the 18th century, for instance, the Archbishop of Taranto ordered several dozen pairs of gloves for the court in St. Petersburg as well as stockings and waistcoats.

No, I have not found any veil-like or transparent tissue made of sea silk anywhere until today. Linea nebula – fog-like linen, or ventus textilis – woven wind, gauze-like, were the names of the finest fabrics made of linen, silk or wool (see Linguistic aspects → Byssus and Byssus). The tarantinidion is often mentioned in connection with sea silk. The transparent garment of the courtesans in ancient Taras, which was supposed to “attract the eyes of male youth and unleash their sensuality”, was probably made from the finest Apulian sheep’s wool. This could be spun so finely that it became a transparent fabric (Sebesta 1994, D’Ippolito 2004).

In literature, the fineness of sea silk is often explained with the argument that a pair of stockings (optionally gloves) fit into a nutshell (optionally snuff box). This legend can probably be traced back to the extremely fine English gloves from Limerick, Ireland, which were in great demand around 1800: “Limerick gloves so delicate that they fit into a walnut shell”. These were gloves made from the very delicate skin of unborn calves (Williams 2010).

To date, all the objects which have been clearly identified as sea silk are neither transparent nor veil-like. The inventory can be used as a convincing element. This might also be the case with the Volto Santo of Manoppello, which is venerated as the face of Christ. The fabric image has become famous worldwide since it was ‘identified’ as a weave of bisso, meaning sea silk. But even here, it is most likely linen byssus (for a detailed analysis see Maeder 2017a).

Knitting

The oldest surviving object made of sea silk, a cap from the 14th century, is knitted. The largest object, a scarf weighing over 400 grams, is also knitted. The most inventoried objects are knitted gloves.

In Taranto around 1800, sea silk was almost exclusively knitted. “Le donne lavorano a maglia calze, berette, guanti ed altre manifatture ricercatissime in oltremonti.” (de Simone 1767), (in English: Women knit hosiery, berets, gloves and other handicrafts that are highly sought after in other parts of the world.) All objects that Archbishop Capecelatro gave away between 1780 and 1789 or ordered for gifts in Taranto between 1802 and 1805 are knitted: Dozens of gloves for men and women, stockings, waistcoats and caps.

“Many mix it with silk, by which the work gets more firmness, but loses that softness and warmth which it has naturally” (Riedesel 1773). This is also confirmed by von Salis Marschlins in 1795. This gives rise to the questions of whether this could relate to the economical use of the precious sea silk. These objects were certainly less expensive than those made of pure sea silk. There must have been more of them – were they therefore not considered worth preserving? In any case, there are very few mixed textiles – almost all the objects inventoried are knitted from pure sea silk.

Many of the knitted objects are extremely fine, like the one of Paris – but not veil-like. The opposite is true since a very special object has not been released to the public until autumn 2019: a lady’s cap in the shape of a turban, very coarse and loosely knitted, 83 grams in weight, originating from southern Italy, probably from the 1920s or 1930s. It was sold in New York by an auction house specialised in textiles.

Weaving

“Jetzt wird die gesponnene Lana Penna fast allgemein gestrickt. … Es scheint aber nicht, dass die Alten dieses Verfahren kannten; die Kleider, welche sie daraus gefertigt haben, müssen gewebt gewesen sein.” (Jolowicz 1861), (in English: Nowadays, the spun Lana Penna is mostly knitted. … But the ancients did not seem to know this process; the clothes they made from it must have been woven.) In literature, many reports about fabrics woven from sea silk can be found. Little of it has survived.

A square tapestry from Apulia is shown at the Esposizione di Napoli in 1853. It was made at the Santa Filomena orphanage in Lecce: “tutto lanapinna con dei piccoli trasparenti de seta agli angoli, e nel mezzo, dentro ghirlanda di fiori, il nome in cifra dell’Augusto nostro Re” (Maestri 1858), (in English: all in sea silk with small silk transparencies at the corners, and in the middle, in a garland of flowers, the name of our King). In 1887, for the occasion of the Golden Jubilee of ordination, Taranto donated a tapestry to Pope Leo XIII (MS-Inventar 66), which had only been known known from descriptions for a long time. Although the Vatican has confirmed receipt of this gift, it was not possible to find it. It has since reappeared – almost completely, only the coat of arms in the middle was removed at some point. A stroke of luck, and a story that remains to be researched.

A large woven scarf from Italo Diana in Sant’Antioco which is made of pure sea silk with woven-in patterns in the form of Templar or paw crosses is a rare and unique piece. There must be more of such woven pieces, because Margherita Raspa, a former student of Italo Diana, remembers having woven a blanket of sea silk that won first prize at an exhibition in Venice. It was made entirely of sea silk that she had spun herself (Flore 2004). Zanetti confirms in 1964: “Si fecero anche stoffe confezionate esclusivamente col bisso, ma con una tecnica tutta particolare, a disegni leggerissimi, sempre ispirati ai motivi ornamentali caratteristici del tessuto d’arte sarda.” (Zanetti 1964), (in English: Fabrics were also made exclusively from sea silk, but with a very special technique, with very light designs, always inspired by the ornamental designs characteristic of Sardinian art fabrics.) The looms used in Sardinia were the same as the ones used on the continent.

In the Krünitz encyclopaedia of 1805, find reports of beautiful woven fabrics that are admired at exhibitions can be found. In Paris in 1801, for instance, “drap de pinne marine, gilets en vigogne et pinne-marine” (Holcroft 1804), in 1806, “tissus fabriqués avec la laine de ce coquillage”, and in 1855, “drap bleu Marie-Louise, mélangé de laine d’Allemagne et de pinne marine”. At an exhibition of goods in Aachen in 1813, sea silk cloth was shown: “par kurze Stückcher blau. Grün mit Pinne Marine melirt” (Lenzmann to Scheibler, letter from 14.8.1813). In 1867, De Simone speaks of woven cloth made from a yarn mixed with sea silk: “Si mescola alla seta nella filatura, quando vuolsi lavorare al telaio per drappo.” With all these fabrics mixed with vicuña or other wool, the question arises as to whether we speak really of sea silk. At the same time, there is talk of imitations. At the end of the 18th century, Dutch factories in Eupen, Montjoie, Verviers, Ensival, a fine, olive-coloured cloth playing in gold was once made – it was intended to imitate the colour of sea silk (Wieck 1851).

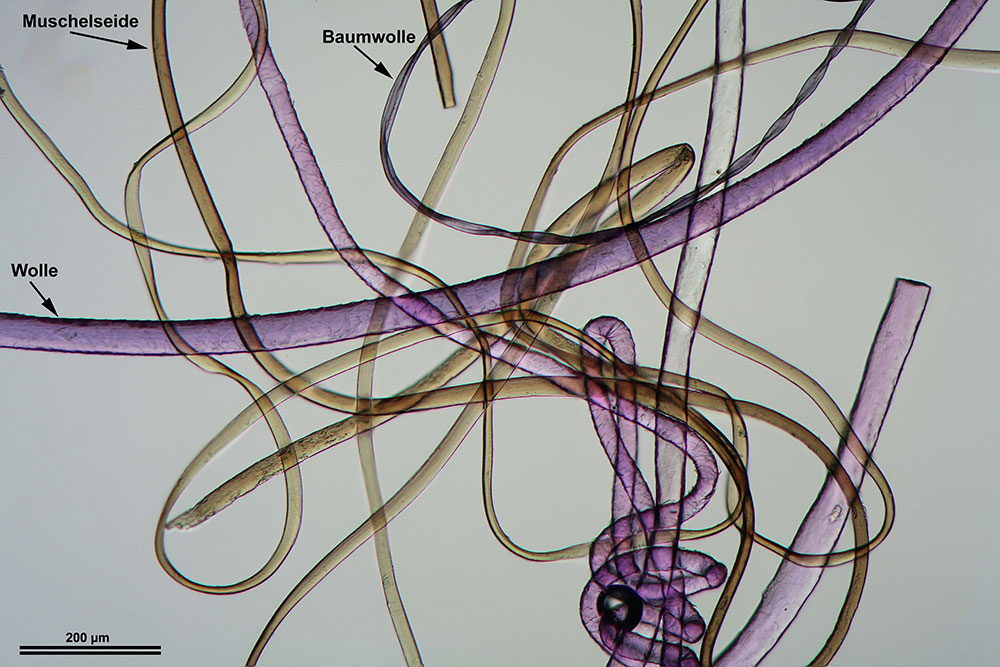

We come a little closer to reality through an analysis of a small woven fragment with felt backing from the Natural History Museum in London. It is a very robust, 1 ½ mm thick double face fabric made of mulberry silk and a very fine wool, which could not be further identified; finest golden sea silk fibres form the surface (Maeder et al. 2019). The Dictionnaire général des tissus anciens et modernes of 1857 describes it perfectly: “L’échantillon … dans lequel la soie de pinne-marine ne fait que le poil, c’est à-dire l’endroit du tissu, a l’aspect d’une peau de bête, d’une grande finesse, telle, par exemple, que le poil de castor.” (In English: The sample … in which the silk of pinna-marina makes up only the surface, has the appearance of a beast’s skin, of great fineness, such as, for instance, the hair of a beaver.)

We found a very similar fragment (MS-Inventar 43) in a cloth pattern book from 1800 in the old textile town of Monschau, in Germany. There the back is made of finest merino wool (Maeder 2013, Sicken 2013). Cashmere and vicuña wool was also mixed with sea silk: “Draps (fab.). Malhout (?), casimirs, double-broche, vigogne et pinne marine” (de La Tynna 1820).

Embroidery and tapestry weaving

In France, as early as the late 18th century, sea silk was woven or embroidered in silk or linen: “… weisse seidene Westen, worin von jener braunen Muschelseide kleine Figuren gewirkt sind” (Krünitz 1805), (in English: white silk waistcoats were made, in which small figures are knitted from that brown sea silk). Tapestries embroidered with sea silk have been produced in Taranto since the middle of the 19th century and have been exhibited at various industrial and commercial exhibitions. Some of these from the 20th century can be seen in Campi 2004 and Strippoli 2004.

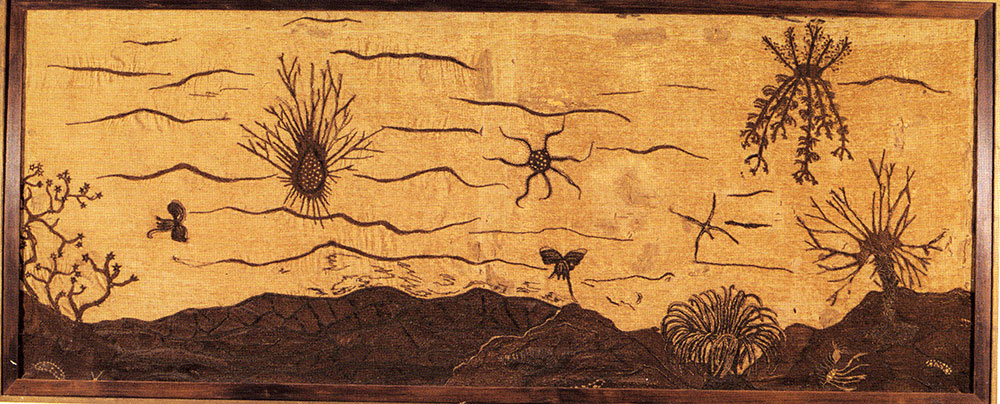

In the first half of the 20th century, Italo Diana in Sant’Antioco wove tapestries on a mulberry silk background with sea silk embroideries, with stylised animals inspired by Byzantine motifs, according to the taste and artistic tradition prevailing on the island (Zanetti 1964).

Besides tapestries, children’s clothes are also preserved. The weave of a pibiones was often used, well-known from Sardinian wool carpets. “Il disegno decorativo, costituito da grani in rilievo, viene creato da un filo di trama supplementare che, fatto passare attraverso i fili dell’ordito, viene ripreso con le mani nei punti in cui si vuole ottenere il disegno e quindi avvolto su un ferro metallico (busa è infatti il ferro da calza), che ne consente l’innalzamento rispetto alla superficie del tessuto.” (Carta Mantiglia 1997), (in English: The decorative design, consisting of embossed grains, is created by an additional weft thread which, when passed through the warp threads, is picked up with the hands at the points where the design is to be achieved and then wrapped on a metal iron which allows it to rise above the surface of the fabric).

At the Istituto statale d’arte in Sassari, there was a Sezione tessitura, where sea silk was also used for multi-coloured tapestries: “…il bisso è di nuovo valorizzato nella confezione di tappeti policromi, nei quali s’inserisce colla sua magica tinta aurea splendente” (Zanetti 1964).

The Pes sisters from Sant’Antioco use two more weaves in addition to a pibiones: punt’e agu, and mostr’ e’ litzus, which is made with very finely spun sea silk yarn. Arianna Pintus weaves sea silk in self-drawn and processed linen in her studio in Tratalias. More about these weavers from Sant’Antioco in the chapter Historical aspects → Modern times → 2000-2020.

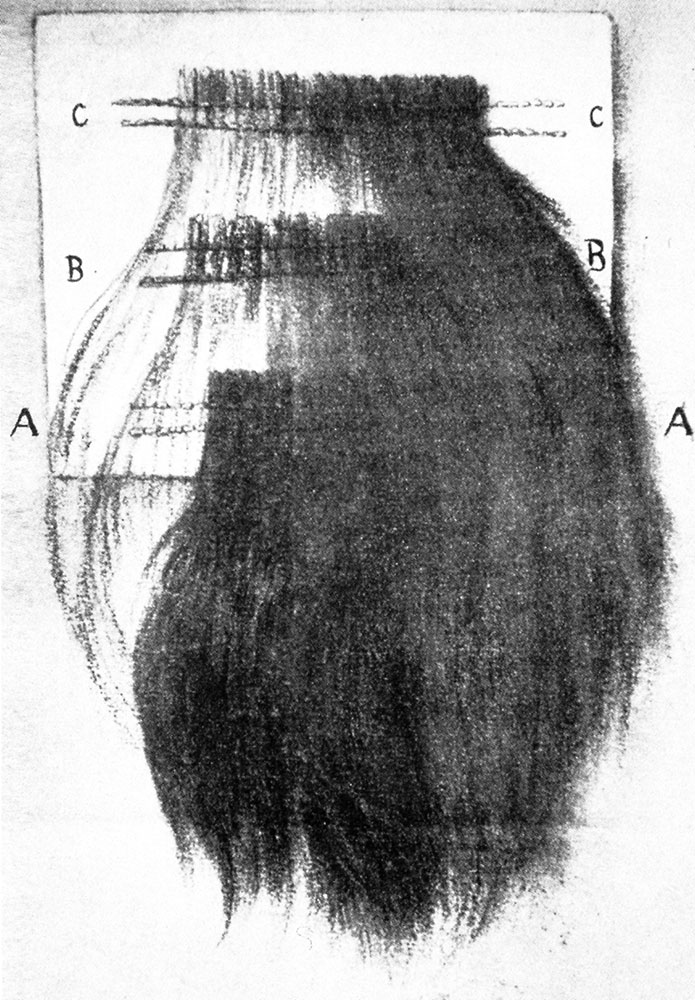

Fur – a pelliccia

In a description of the 1873 World’s Fair in Vienna, we read: “In den Hallen, die Italien einnimmt, ist ein Kragen, eine Muffe und einiges Andere, aus einer blondbraunen Faser gefertigt, ausgestellt. Diese Fasermasse ist in Plüschbindung verwebt und verleiht den Gegenständen ein pelzartiges Aussehen. Aber der eigentümliche matte und doch volle Glanz passt nicht zur Auslegung, dass dies, Thierfell sei.” (Grothe 1873), (in English: In the halls that Italy occupies, a collar, a muff and some other things made of a blonde-brown fibre are exhibited. This fibre is woven in plush weave and gives the objects a fur-like appearance. But the peculiar matte yet full lustre does not fit the interpretation that this is animal fur). No, it was not an animal fur, but a new processing method for sea silk introduced in Taranto in the early 19th century, which also found favour in Sardinia at the end of the century. In 1916, Basso-Arnoux described how to make such a fur in detail and added drawings of the instruments required for this.

In 1928, Mastrocinque describes the production process, which brings out the golden sheen of the sea silk. In this process, whole beards of cleaned and combed fibres, where the remains of the foot have not been completely cut off, are sewn onto a lower weave from bottom to top, closely together and overlapping. A muff a pellicia from the Santa Filomena orphanage in Lecce, was awarded a gold medal at the Esposizione di Napoli in 1853.

Cleaned, combed fibre beards were also made into passementerie, cord ends and jewelry, as the inventory shows.